I wandered lonely as a Cloud

That floats on high o’er Vales and Hills,

When all at once I saw a crowd,

A host of golden Daffodils;

Beside the Lake, beneath the trees,

Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.

Continuous as the stars that shine

And twinkle on the milky way,

They stretched in never-ending line

Along the margin of a bay:

Ten thousand saw I at a glance,

Tossing their heads in sprightly dance.

The waves beside them danced, but they

Out-did the sparkling waves in glee:—

A Poet could not but be gay

In such a jocund company:

I gazed—and gazed—but little thought

What wealth the shew to me had brought:

For oft when on my couch I lie

In vacant or in pensive mood,

They flash upon that inward eye

Which is the bliss of solitude,

And then my heart with pleasure fills,

And dances with the Daffodils.

I wandered lonely as a cloud

That floats on high o'er vales and hills,

When all at once I saw a crowd,

A host, of golden daffodils;

Beside the lake, beneath the trees,

Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.

Continuous as the stars that shine

And twinkle on the milky way,

They stretched in never-ending line

Along the margin of a bay:

Ten thousand saw I at a glance,

Tossing their heads in sprightly dance.

The waves beside them danced; but they

Out-did the sparkling waves in glee:

A poet could not but be gay,

In such a jocund company:

I gazed—and gazed—but little thought

What wealth the show to me had brought:

For oft, when on my couch I lie

In vacant or in pensive mood,

They flash upon that inward eye

Which is the bliss of solitude;

And then my heart with pleasure fills,

And dances with the daffodils.

.

William Wordsworth (1815)

That floats on high o’er Vales and Hills,

When all at once I saw a crowd,

A host of golden Daffodils;

Beside the Lake, beneath the trees,

Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.

Continuous as the stars that shine

And twinkle on the milky way,

They stretched in never-ending line

Along the margin of a bay:

Ten thousand saw I at a glance,

Tossing their heads in sprightly dance.

The waves beside them danced, but they

Out-did the sparkling waves in glee:—

A Poet could not but be gay

In such a jocund company:

I gazed—and gazed—but little thought

What wealth the shew to me had brought:

For oft when on my couch I lie

In vacant or in pensive mood,

They flash upon that inward eye

Which is the bliss of solitude,

And then my heart with pleasure fills,

And dances with the Daffodils.

I wandered lonely as a cloud

That floats on high o'er vales and hills,

When all at once I saw a crowd,

A host, of golden daffodils;

Beside the lake, beneath the trees,

Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.

Continuous as the stars that shine

And twinkle on the milky way,

They stretched in never-ending line

Along the margin of a bay:

Ten thousand saw I at a glance,

Tossing their heads in sprightly dance.

The waves beside them danced; but they

Out-did the sparkling waves in glee:

A poet could not but be gay,

In such a jocund company:

I gazed—and gazed—but little thought

What wealth the show to me had brought:

For oft, when on my couch I lie

In vacant or in pensive mood,

They flash upon that inward eye

Which is the bliss of solitude;

And then my heart with pleasure fills,

And dances with the daffodils.

.

"I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud" (also commonly known as "Daffodils") is a lyric poem by William Wordsworth. It is Wordsworth's most famous work.

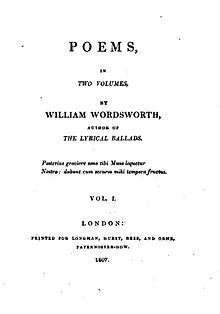

The poem was inspired by an event on 15 April 1802, in which Wordsworth and his sister Dorothy came across a "long belt" of daffodils. Written some time between 1804 and 1807 (in 1804 by Wordsworth's own account), it was first published in 1807 in Poems in Two Volumes, and a revised version was published in 1815.

In a poll conducted in 1995 by the BBC Radio 4 Bookworm programme to determine the nation's favourite poems, I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud came fifth. Often anthologised, the poem is commonly seen as a classic of English romantic poetry, although Poems in Two Volumes, in which it first appeared, was poorly reviewed by Wordsworth's contemporaries.

Background

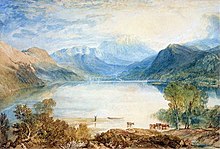

The inspiration for the poem came from a walk Wordsworth took with his sister Dorothy around Glencoyne Bay, Ullswater, in the Lake District. He would draw on this to compose "I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud" in 1804, inspired by Dorothy's journal entry describing the walk:

At the time he wrote the poem, Wordsworth was living with his wife, Mary Hutchinson, and sister Dorothy at Town End, in Grasmere in England's Lake District. Mary contributed what Wordsworth later said were the two best lines in the poem, recalling the "tranquil restoration" of Tintern Abbey,

- They flash upon that inward eye

- Which is the bliss of solitude

Wordsworth was aware of the appropriateness of the idea of daffodils which “flash upon that inward eye” because in his 1815 version he added a note commenting on the “flash” as an “ocular spectrum”. Coleridge in Biographia Literaria of 1817, while he acknowledging the concept of “visual spectrum” as being “well known”, described Wordsworth’s (and Mary’s) lines, amongst others, as “mental bombast”. Fred Blick, has shown that the idea of flashing flowers was derived from the “Elizabeth Linnaeus Phenomenon”, so-called because of the discovery of flashing flowers by Elizabeth Linnaeus in 1762. The phenomenon was reported upon in 1789 and 1794 by Erasmus Darwin, whose work Wordsworth certainly read.

The entire household thus contributed to the poem. Nevertheless, Wordsworth's biographer Mary Moorman, notes that Dorothy was excluded from the poem, even though she had seen the daffodils together with Wordsworth. The poem itself was placed in a section of Poems in Two Volumes entitled Moods of my Mind in which he grouped together his most deeply felt lyrics. Others included To a Butterfly, a childhood recollection of chasing butterflies with Dorothy, and The Sparrow's Nest, in which he says of Dorothy "She gave me eyes, she gave me ears".

The earlier Lyrical Ballads, a collection of poems by both himself and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, had been first published in 1798 and had started the romantic movement in England. It had brought Wordsworth and the other Lake poets into the poetic limelight. Wordsworth had published nothing new since the 1800 edition of Lyrical Ballads, and a new publication was eagerly awaited. Wordsworth had, however, gained some financial security by the 1805 publication of the fourth edition of Lyrical Ballads; it was the first from which he enjoyed the profits of copyright ownership. He decided to turn away from the long poem he was working on (The Recluse) and devote more attention to publishing Poems in Two Volumes, in which "I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud" first appeared.

Revised version

Wordsworth revised the poem in 1815. He replaced "dancing" with "golden"; "along" with "beside"; and "ten thousand" with "fluttering and". He then added a stanza between the first and second, and changed "laughing" to "jocund". The last stanza was left untouched.

The plot of the poem is simple. In the 1815 revision, Wordsworth described it as "rather an elementary feeling and simple impression (approaching to the nature of an ocular spectrum) upon the imaginative faculty, rather than an exertion of it..."

- I wandered lonely as a cloud

- That floats on high o'er vales and hills,

- When all at once I saw a crowd,

- A host of golden daffodils;

- Beside the lake, beneath the trees,

- Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.

- Continuous as the stars that shine

- and twinkle on the Milky Way,

- They stretched in never-ending line

- along the margin of a bay:

- Ten thousand saw I at a glance,

- tossing their heads in sprightly dance.

- The waves beside them danced; but they

- Out-did the sparkling waves in glee:

- A poet could not but be gay,

- in such a jocund company:

- I gazed—and gazed—but little thought

- what wealth the show to me had brought:

- For oft, when on my couch I lie

- In vacant or in pensive mood,

- They flash upon that inward eye

- Which is the bliss of solitude;

- And then my heart with pleasure fills,

- And dances with the daffodils.

Pamela Woof notes "The permanence of stars as compared with flowers emphasises the permanence of memory for the poet."

Andrew Motion notes that the final verse replicates in the minds of its readers the very experience it describes

Reception

Contemporary

Poems in Two Volumes was poorly reviewed by Wordsworth's contemporaries, including Lord Byron, whom Wordsworth came to despise.Byron said of the volume, in one of its first reviews, "Mr. W[ordsworth] ceases to please, ... clothing [his ideas] in language not simple, but puerile".Wordsworth himself wrote ahead to soften the thoughts of The Critical Review, hoping his friend Francis Wrangham would push for a softer approach. He succeeded in preventing a known enemy from writing the review, but it didn't help; as Wordsworth himself said, it was a case of "Out of the frying pan, into the fire". Of any positives within Poems in Two Volumes, the perceived masculinity in The Happy Warrior, written on the death of Nelson and unlikely to be the subject of attack, was one such. Poems like "I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud" could not have been further from it. Wordsworth took the reviews stoically.

Even Wordsworth's close friend Samuel Taylor Coleridge said (referring especially to the "child-philosopher" stanzas VII and VIII of Intimations of Immortality) that the poems contained "mental bombast". Two years later, however, many were more positive about the collection. Samuel Rogers said that he had "dwelt particularly on the beautiful idea of the 'Dancing Daffodils'", and this was echoed by Henry Crabb Robinson. Critics were rebutted by public opinion, and the work gained in popularity and recognition, as did Wordsworth.

Poems in Two Volumes was savagely reviewed by Francis Jeffrey in the Edinburgh Review (without, however, singling out "I wandered lonely as a Cloud"), but the Review was well known for its dislike of the Lake poets. As Sir Walter Scott put it at the time of the poem's publication, "Wordsworth is harshly treated in the Edinburgh Review, but Jeffrey gives ... as much praise as he usually does", and indeed Jeffrey praised the sonnets.[21]

Upon the author's death in 1850, the Westminster Review called "I wandered lonely as a Cloud" "very exquisite".

Modern usage

The poem is presented and taught in many schools in the English-speaking world: these include the 7th grade of most schools of the Indian Certificate of Secondary Education (ICSE), India; the English Literature GCSE course in some examination boards in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland; and in the current Higher School Certificate syllabus topic, Inner Journeys, New South Wales, Australia. It is also frequently used as a part of the Junior Certificate English Course in Ireland as part of the Poetry Section. In The Middle Passage, V.S.Naipaul refers to a campaign in Trinidad against the use of the poem as a set text because daffodils do not grow in the tropics.

Because it is one of the best known poems in the English language, it has frequently been the subject of parody and satire.

The English Prog Rock band Genesis parodies the poem in the opening lyrics to the song "The Colony of Slippermen", from their 1974 album The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway.

It was the subject of a 1985 Heineken beer TV advertisement, which depicts a poet having difficulties with his opening lines, only able to come up with I walked about a bit on my ownor I strolled around without anyone else until downing a Heineken and reaching the immortal "I wandered lonely as a Cloud" (because "Heineken refreshes the poets other beers can't reach"). The assertion that Wordsworth originally hit on "I wandered lonely as a cow" until Dorothy told him "William, you can't put that" occasionally finds its way into print.

Daffodil tourism

The daffodils Wordsworth saw would have been wild daffodils. However, the National Gardens Scheme runs a Daffodil Day every year, allowing visitors to view daffodils in Cumbrian gardens including Dora's Field, which was planted by Wordsworth. In 2013 the event was held in March, when unusually cold weather meant that relatively few of the plants were in flower. April, the month that Wordsworth saw the daffodils at Ullswater, is usually a good time to view them, although the Lake District climate has changed since the poem was written.

Anniversaries

In 2004, in celebration of the 200th anniversary of the writing of the poem, it was also read aloud by 150,000 British schoolchildren, aimed both at improving recognition of poetry, and in support of Marie Curie Cancer Care.

In 2007, Cumbria Tourism released a rap version of the poem, featuring MC Nuts, a Lake District Red squirrel, in an attempt to capture the "YouTube generation" and attract tourists to the Lake District. Published on the two-hundredth anniversary of the original, it attracted wide media attention.] It was welcomed by the Wordsworth Trust, but attracted the disapproval of some commentators.

In 2015 events marking the 200th anniversary of the publication of the revised version were celebrated at Rydal Mount.

In popular culture

In the 2013 musical Big Fish (musical), composed by Andrew Lippa, some lines from the poem are used in the song "Daffodils," which concludes the first act. Lippa mentioned this in a video created by Broadway.com in the same year.

William Wordsworth (7 April 1770 – 23 April 1850) was a major English Romantic poet who, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, helped to launch the Romantic Age in English literature with their joint publication Lyrical Ballads (1798).

Wordsworth's magnum opus is generally considered to be The Prelude, a semi-autobiographical poem of his early years that he revised and expanded a number of times. It was posthumously titled and published, before which it was generally known as "the poem to Coleridge". Wordsworth was Britain's poet laureate from 1843 until his death from pleurisy on 23 April 1850.

The second of five children born to John Wordsworth and Ann Cookson, William Wordsworth was born on 7 April 1770 in Wordsworth House in Cockermouth, Cumberland, part of the scenic region in northwestern England known as the Lake District. His sister, the poet and diarist Dorothy Wordsworth, to whom he was close all his life, was born the following year, and the two were baptised together. They had three other siblings: Richard, the eldest, who became a lawyer; John, born after Dorothy, who went to sea and died in 1805 when the ship of which he was captain, the Earl of Abergavenny, was wrecked off the south coast of England; and Christopher, the youngest, who entered the Church and rose to be Master of Trinity College, Cambridge.

Wordsworth's father was a legal representative of James Lowther, 1st Earl of Lonsdale and, through his connections, lived in a large mansion in the small town. He was frequently away from home on business, so the young William and his siblings had little involvement with him and remained distant from him until his death in 1783. However, he did encourage William in his reading, and in particular set him to commit to memory large portions of verse, including works by Milton, Shakespeare and Spenser. William was also allowed to use his father's library. William also spent time at his mother's parents' house in Penrith, Cumberland, where he was exposed to the moors, but did not get along with his grandparents or his uncle, who also lived there. His hostile interactions with them distressed him to the point of contemplating suicide.

Wordsworth was taught to read by his mother and attended, first, a tiny school of low quality in Cockermouth, then a school in Penrith for the children of upper-class families, where he was taught by Ann Birkett, who insisted on instilling in her students traditions that included pursuing both scholarly and local activities, especially the festivals around Easter, May Day and Shrove Tuesday. Wordsworth was taught both the Bible and the Spectator, but little else. It was at the school in Penrith that he met the Hutchinsons, including Mary, who later became his wife

After the death of his mother, in 1778, Wordsworth's father sent him to Hawkshead Grammar School in Lancashire (now in Cumbria) and sent Dorothy to live with relatives in Yorkshire. She and William did not meet again for another nine years.

Wordsworth made his debut as a writer in 1787 when he published a sonnet in The European Magazine. That same year he began attending St John's College, Cambridge. He received his BA degree in 1791. He returned to Hawkshead for the first two summers of his time at Cambridge, and often spent later holidays on walking tours, visiting places famous for the beauty of their landscape. In 1790 he went on a walking tour of Europe, during which he toured the Alps extensively, and visited nearby areas of France, Switzerland, and Italy.