Unacquainted tones

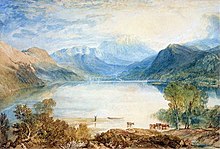

Unfamiliar light

Artist steps off

Free flight

Cannot breath

Need reprieve

Needle pricks

And stitches

Cries embrace

A weeping face

Rhythms meeting

And leaving

Stinging pains

Painted stains

Crashing waves

And heart songs

Words jumbled

Phrases crumbled

Lost and blocked

In swelling sea

Unfamiliar light

Artist steps off

Free flight

Cannot breath

Need reprieve

Needle pricks

And stitches

Cries embrace

A weeping face

Rhythms meeting

And leaving

Stinging pains

Painted stains

Crashing waves

And heart songs

Words jumbled

Phrases crumbled

Lost and blocked

In swelling sea