Stephen Darori is the Bard of Bat Yam, Poet Laureate of Zion Digital Campaign Head f many cause No friend or admirer of #OtVeyDonaldTrump Hey Ho #ImpeachHimNow. Stephen is a Marketing and Financial Whiz, Journalist, Editor Strategist, Gourmet and Cat Lover . You can find Stephen Darori on Linkedin, Facebook and Twitter .

Tuesday, December 19, 2017

Batouchka ,are you Mrs. Right Darori?

‘The Good-Morrow’ by John Dunn one of the Bard of Bat Yam, POet Laureate of Zion's favourite poems

I wonder, by my troth, what thou and I

Did, till we loved? Were we not weaned till then?

But sucked on country pleasures, childishly?

Or snorted we in the Seven Sleepers’ den?

’Twas so; but this, all pleasures fancies be.

If ever any beauty I did see,

Which I desired, and got, ’twas but a dream of thee.

And now good-morrow to our waking souls,

Which watch not one another out of fear;

For love, all love of other sights controls,

And makes one little room an everywhere.

Let sea-discoverers to new worlds have gone,

Let maps to other, worlds on worlds have shown,

Let us possess one world, each hath one, and is one.

My face in thine eye, thine in mine appears,

And true plain hearts do in the faces rest;

Where can we find two better hemispheres,

Without sharp north, without declining west?

Whatever dies, was not mixed equally;

If our two loves be one, or, thou and I

Love so alike, that none do slacken, none can die.

‘I wonder, by my troth, what thou and I / Did, till we loved?’ With these frank and informal words, John Donne (1572-1631) begins one of his most remarkable poems, a poem often associated – as is much of Donne’s work – with the Metaphysical ‘school’ of English poets. But what is ‘The Good-Morrow’ actually about? In this post, we offer some notes towards an analysis of Donne’s ‘The Good-Morrow’ in terms of its language, meaning, and themes.

A brief summary of Donne’s poem might be helpful to start with. In the first stanza, he addresses his beloved and asks her to cast her mind back to before they were lovers. What was their existence like before they met and loved each other? Were they little more than babies, like infants who are not yet weaned off their mother’s breast? (‘Country pleasures’ has the same punning suggestion it carries in Shakespeare’s plays, such as Hamlet’s ‘country

matters’: we are invited to concentrate on the first syllable of ‘country’.) Or, if not like children, were the two of them – the poet and his lover – asleep before they met? (‘Snorted’ here means ‘snored’.) Donne answers his own (rhetorical) questions by saying yes: before they met each other, any pleasures they enjoyed, or thought they enjoyed, were mere a mere shadow of the joy they now feel in each other’s company.

In the second stanza, Donne bids good morning, or good day (hence ‘The Good-Morrow’) to his and his lover’s souls, now waking from their ‘dream’ and experiencing real love. They look at each other, but not through fear or jealousy, but because they like to look at each other. Indeed, the sight of each other far exceeds any fondness they have for other pleasant sights, and the bedroom where they spend their time (they are newly loved up, after all!) has become their world: the real world beyond their bedroom is of little interest to them. Men may voyage across the sea to other lands, and men may even chart the locations of other worlds beyond our own – that is of no concern to us, Donne tells his lover. We don’t need those other worlds, because our bodies are a world in themselves, ready for the other to explore. This is what Donne means by ‘worlds on worlds’ and ‘each hath one, and is one’: he and his lover, he urges, should enjoy a bit of ‘world-on-world action’. His body is a new world for his beloved to explore, and her body is a world for him to possess and explore.

In the final stanza, Donne zooms in even further from the bodies of the two lovebirds, focusing on their eyes: he sees his face reflected in his lover’s eye, and her face appears in his eyes (meaning not only that she sees herself reflected in Donne’s eyes, but also that as he turns to face her she is in his line of vision). Their very hearts are exposed to each other, their devotion to each other plain in their expressions. (The eyes never lie and all that.) Donne then uses the metaphor of ‘hemispheres’ – half-worlds (worlds again!) – to convey the idea that she is his ‘other half’ and he hers. But in fact, Donne argues, his and his lover’s ‘hemispheres’ are better than the hemispheres that make up the Earth, since their love has no cold North Pole and no ‘declining West’ (suggesting that the sun will never set on their love for each other). Donne then throws in some alchemy for good measure, stating that ‘Whatever dies was not mixed equally’ – although this line might also be read as a reference to the male and female ‘seed’, which, according to mainstream medical theory at the time, had to be equally mixed if conception were to take place. Donne then concludes by saying that if their love for each other is felt equally strongly on both sides, then their love is strong and cannot die.

Even summarising ‘The Good-Morrow’ becomes a task of annotation and discussion, but then that’s so often the mark of a rich and complex poem. How should we interpret and analyse the poem’s meaning? It’s clearly a celebration of young love and a very candid depiction of two lovers sharing their bodies with each other. Like so

many of Donne’s love poems, it takes us right into the bedroom, ‘between the sheets’ (as Simon Schama put it in a BBC documentary about John Donne). Most poets stop short of bringing us into the bedroom with them. Donne wants us right there between him and his beloved.

We’ll conclude this short introduction to, and analysis of, ‘The Good-Morrow’ with a few more glosses which readers may find of interest. In the first stanza, Donne likens himself and his lover to the Seven Sleepers, who were seven Christians sealed in a cave by the Roman Emperor Decius – who had a penchant for persecuting Christians – in around the year AD 250. These Christians reportedly slept for nearly 200 years before being woken up to find Christianity had become a world religion. The point of Donne’s analogy is that the love he and his lover feel for each other is like a new religion, that’s how devoted they are.

In the second stanza, Donne refers both to sea-travel to new worlds: the New World of the Americas was just being explored and colonised at this time, by England and Spain, chiefly. But Donne also suggests, when he writes of ‘maps to others’, that man is charting other worlds too: when Donne was writing, the revolution in astronomy was just underway, and Copernicus’ theory that the earth travelled around the sun (rather than vice versa) was being explored by Johannes Kepler and, slightly later, Galileo. As the twentieth-century poet and critic William Empson pointed out in ‘Donne the Space Man’, John Donne was peculiarly interested in travelling to other planets, and his poetry reflects this, making him unique among Elizabethan and Jacobean poets.

This is yet another reason to revere him, and in this summary and analysis of ‘The Good-Morrow’ we’ve tried to get across some of the richness and strangeness of Donne’s classic poem. What do you make of ‘The Good-Morrow’?

Did, till we loved? Were we not weaned till then?

But sucked on country pleasures, childishly?

Or snorted we in the Seven Sleepers’ den?

’Twas so; but this, all pleasures fancies be.

If ever any beauty I did see,

Which I desired, and got, ’twas but a dream of thee.

And now good-morrow to our waking souls,

Which watch not one another out of fear;

For love, all love of other sights controls,

And makes one little room an everywhere.

Let sea-discoverers to new worlds have gone,

Let maps to other, worlds on worlds have shown,

Let us possess one world, each hath one, and is one.

My face in thine eye, thine in mine appears,

And true plain hearts do in the faces rest;

Where can we find two better hemispheres,

Without sharp north, without declining west?

Whatever dies, was not mixed equally;

If our two loves be one, or, thou and I

Love so alike, that none do slacken, none can die.

‘I wonder, by my troth, what thou and I / Did, till we loved?’ With these frank and informal words, John Donne (1572-1631) begins one of his most remarkable poems, a poem often associated – as is much of Donne’s work – with the Metaphysical ‘school’ of English poets. But what is ‘The Good-Morrow’ actually about? In this post, we offer some notes towards an analysis of Donne’s ‘The Good-Morrow’ in terms of its language, meaning, and themes.

A brief summary of Donne’s poem might be helpful to start with. In the first stanza, he addresses his beloved and asks her to cast her mind back to before they were lovers. What was their existence like before they met and loved each other? Were they little more than babies, like infants who are not yet weaned off their mother’s breast? (‘Country pleasures’ has the same punning suggestion it carries in Shakespeare’s plays, such as Hamlet’s ‘country

matters’: we are invited to concentrate on the first syllable of ‘country’.) Or, if not like children, were the two of them – the poet and his lover – asleep before they met? (‘Snorted’ here means ‘snored’.) Donne answers his own (rhetorical) questions by saying yes: before they met each other, any pleasures they enjoyed, or thought they enjoyed, were mere a mere shadow of the joy they now feel in each other’s company.

In the second stanza, Donne bids good morning, or good day (hence ‘The Good-Morrow’) to his and his lover’s souls, now waking from their ‘dream’ and experiencing real love. They look at each other, but not through fear or jealousy, but because they like to look at each other. Indeed, the sight of each other far exceeds any fondness they have for other pleasant sights, and the bedroom where they spend their time (they are newly loved up, after all!) has become their world: the real world beyond their bedroom is of little interest to them. Men may voyage across the sea to other lands, and men may even chart the locations of other worlds beyond our own – that is of no concern to us, Donne tells his lover. We don’t need those other worlds, because our bodies are a world in themselves, ready for the other to explore. This is what Donne means by ‘worlds on worlds’ and ‘each hath one, and is one’: he and his lover, he urges, should enjoy a bit of ‘world-on-world action’. His body is a new world for his beloved to explore, and her body is a world for him to possess and explore.

In the final stanza, Donne zooms in even further from the bodies of the two lovebirds, focusing on their eyes: he sees his face reflected in his lover’s eye, and her face appears in his eyes (meaning not only that she sees herself reflected in Donne’s eyes, but also that as he turns to face her she is in his line of vision). Their very hearts are exposed to each other, their devotion to each other plain in their expressions. (The eyes never lie and all that.) Donne then uses the metaphor of ‘hemispheres’ – half-worlds (worlds again!) – to convey the idea that she is his ‘other half’ and he hers. But in fact, Donne argues, his and his lover’s ‘hemispheres’ are better than the hemispheres that make up the Earth, since their love has no cold North Pole and no ‘declining West’ (suggesting that the sun will never set on their love for each other). Donne then throws in some alchemy for good measure, stating that ‘Whatever dies was not mixed equally’ – although this line might also be read as a reference to the male and female ‘seed’, which, according to mainstream medical theory at the time, had to be equally mixed if conception were to take place. Donne then concludes by saying that if their love for each other is felt equally strongly on both sides, then their love is strong and cannot die.

Even summarising ‘The Good-Morrow’ becomes a task of annotation and discussion, but then that’s so often the mark of a rich and complex poem. How should we interpret and analyse the poem’s meaning? It’s clearly a celebration of young love and a very candid depiction of two lovers sharing their bodies with each other. Like so

many of Donne’s love poems, it takes us right into the bedroom, ‘between the sheets’ (as Simon Schama put it in a BBC documentary about John Donne). Most poets stop short of bringing us into the bedroom with them. Donne wants us right there between him and his beloved.

We’ll conclude this short introduction to, and analysis of, ‘The Good-Morrow’ with a few more glosses which readers may find of interest. In the first stanza, Donne likens himself and his lover to the Seven Sleepers, who were seven Christians sealed in a cave by the Roman Emperor Decius – who had a penchant for persecuting Christians – in around the year AD 250. These Christians reportedly slept for nearly 200 years before being woken up to find Christianity had become a world religion. The point of Donne’s analogy is that the love he and his lover feel for each other is like a new religion, that’s how devoted they are.

In the second stanza, Donne refers both to sea-travel to new worlds: the New World of the Americas was just being explored and colonised at this time, by England and Spain, chiefly. But Donne also suggests, when he writes of ‘maps to others’, that man is charting other worlds too: when Donne was writing, the revolution in astronomy was just underway, and Copernicus’ theory that the earth travelled around the sun (rather than vice versa) was being explored by Johannes Kepler and, slightly later, Galileo. As the twentieth-century poet and critic William Empson pointed out in ‘Donne the Space Man’, John Donne was peculiarly interested in travelling to other planets, and his poetry reflects this, making him unique among Elizabethan and Jacobean poets.

This is yet another reason to revere him, and in this summary and analysis of ‘The Good-Morrow’ we’ve tried to get across some of the richness and strangeness of Donne’s classic poem. What do you make of ‘The Good-Morrow’?

Saturday, December 2, 2017

A Psalm Of Life By Henry Wadsworth Longfellow ... one of the favourite poems of the Bard of Bat am, Poet Laureate of Zion

Tell me not, in mournful numbers,

Life is but an empty dream!—

For the soul is dead that slumbers,

And things are not what they seem.

Life is real! Life is earnest!

And the grave is not its goal;

Dust thou art, to dust returnest,

Was not spoken of the soul.

Not enjoyment, and not sorrow,

Is our destined end or way;

But to act, that each to-morrow

Find us farther than to-day.

Art is long, and Time is fleeting,

And our hearts, though stout and brave,

Still, like muffled drums, are beating

Funeral marches to the grave.

In the world's broad field of battle,

In the bivouac of Life,

Be not like dumb, driven cattle!

Be a hero in the strife!

Trust no Future, howe'er pleasant!

Let the dead Past bury its dead!

Act,—act in the living Present!

Heart within, and God o'erhead!

Lives of great men all remind us

We can make our lives sublime,

And, departing, leave behind us

Footprints on the sands of time;

Footprints, that perhaps another,

Sailing o'er life's solemn main,

A forlorn and shipwrecked brother,

Seeing, shall take heart again.

Let us, then, be up and doing,

With a heart for any fate;

Still achieving, still pursuing,

Learn to labor and to wait.

"A Psalm of Life" is a poem written by American writer Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, often subtitled "What the Heart of the Young Man Said to the Psalmist"

Composition and publication history

Longfellow wrote the poem shortly after completing lectures on German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and was heavily inspired by him. He was also inspired to write it by a heartfelt conversation he had with friend and fellow professor at Harvard University Cornelius Conway Felton; the two had spent an evening "talking of matters, which lie near one's soul:–and how to bear one's self doughtily in Life's battle: and make the best of things".. The next day, he wrote "A Psalm of Life". Longfellow was further inspired by the death of his first wife, Mary Storer Potter, and attempted to convince himself to have "a heart for any fate".

The poem was first published in the October 1838 issue of The Knickerbocker,[1] though it was attributed only to "L." Longfellow was promised five dollars for its publication, though he never received payment. This original publication also included a slightly altered quote from Richard Crashaw as an epigram: "Life that shall send / A challenge to its end, / And when it comes, say, 'Welcome, friend.'" "A Psalm of Life" and other early poems by Longfellow, including "The Village Blacksmith" and "The Wreck of the Hesperus", were collected and published as Voices of the Night in 1839. This volume sold for 75 cents and, by 1842, had gone into six editions.

In the summer of 1838, Longfellow wrote "The Light of Stars", a poem which he called "A Second Psalm of Life". His 1839 poem inspired by the death of his wife, "Footsteps of Angels", was similarly referred to as "Voices of the Night: A Third Psalm of Life". Another poem published in Voices of the Night titled "The Reaper and the Flowers" was originally subtitled "A Psalm of Death".

Analysis

The poem, written in an ABAB pattern, is meant to inspire its readers to live actively, and neither to lament the past nor to take the future for granted. The didactic message is underscored by a vigorous trochaic meter and frequent exclamation. Answering a reader's question about the poem in 1879, Longfellow himself summarized that the poem was "a transcript of my thoughts and feelings at the time I wrote, and of the conviction therein expressed, that Life is something more than an idle dream."Richard Henry Stoddard referred to the theme of the poem as a "lesson of endurance".

Longfellow wrote "A Psalm of Life" at the beginning of a period in which he showed an interest in the Judaic, particularly strong in the 1840s and 1850s. More specifically, Longfellow looked at the American versions or American responses to Jewish stories. Most notable in this strain is the poet's "The Jewish Cemetery at Newport", inspired by the Touro Cemeteryin Newport, Rhode Island.

Further, the influence of Goethe was noticeable. In 1854, an English acquaintance suggested "A Psalm of Life" was merely a translation. Longfellow denied this, but admitted he may have had some inspiration from him as he was writing "at the beginning of my life poetical, when a thousand songs were ringing in my ears; and doubtless many echoes and suggestions will be found in them. Let the fact go for what it is worth".

Response

"A Psalm of Life" became a popular and oft-quoted poem, such that Longfellow biographer Charles Calhoun noted it had risen beyond being a poem and into a cultural artifact. Among its many quoted lines are "footprints on the sands of time".In 1850, Longfellow recorded in his journal of his delight upon hearing it quoted by a minister in a sermon, though he was disappointed when no member of the congregation could identify the source.] Not long after Longfellow's death, biographer Eric S. Robertson noted, "The 'Psalm of Life,' great poem or not, went straight to the hearts of the people, and found an echoing shout in their midst. From the American pulpits, right and left, preachers talked to the people about it, and it came to be sung as a hymn in churches." The poem was widely translated into a variety of languages, including Sanskrit.] Joseph Massel translated the poem, as well as others from Longfellow's later collection Tales of a Wayside Inn, into Hebrew.

Calhoun also notes that "A Psalm of Life" has become one of the most frequently memorized and most ridiculed of English poems, with an ending reflecting "Victorian cheeriness at its worst". Modern critics have dismissed its "sugar-coated pill" promoting a false sense of security. One story has it that a man once approached Longfellow and told him that a worn, hand-written copy of "A Psalm of Life" saved him from suicide.] Nevertheless, Longfellow scholar Robert L. Gale referred to "A Psalm of Life" as "the most popular poem ever written in English". Edwin Arlington Robinson, an admirer of Longfellow's, likely was referring to this poem in his "Ballade by the Fire" with his line, "Be up, my soul". Despite Longfellow's dwindling reputation among modern readers and critics, "A Psalm of Life" remains one of the few of his poems still anthologized.

"A Psalm of Life" became a popular and oft-quoted poem, such that Longfellow biographer Charles Calhoun noted it had risen beyond being a poem and into a cultural artifact. Among its many quoted lines are "footprints on the sands of time".In 1850, Longfellow recorded in his journal of his delight upon hearing it quoted by a minister in a sermon, though he was disappointed when no member of the congregation could identify the source.] Not long after Longfellow's death, biographer Eric S. Robertson noted, "The 'Psalm of Life,' great poem or not, went straight to the hearts of the people, and found an echoing shout in their midst. From the American pulpits, right and left, preachers talked to the people about it, and it came to be sung as a hymn in churches." The poem was widely translated into a variety of languages, including Sanskrit.] Joseph Massel translated the poem, as well as others from Longfellow's later collection Tales of a Wayside Inn, into Hebrew.

Calhoun also notes that "A Psalm of Life" has become one of the most frequently memorized and most ridiculed of English poems, with an ending reflecting "Victorian cheeriness at its worst". Modern critics have dismissed its "sugar-coated pill" promoting a false sense of security. One story has it that a man once approached Longfellow and told him that a worn, hand-written copy of "A Psalm of Life" saved him from suicide.] Nevertheless, Longfellow scholar Robert L. Gale referred to "A Psalm of Life" as "the most popular poem ever written in English". Edwin Arlington Robinson, an admirer of Longfellow's, likely was referring to this poem in his "Ballade by the Fire" with his line, "Be up, my soul". Despite Longfellow's dwindling reputation among modern readers and critics, "A Psalm of Life" remains one of the few of his poems still anthologized.

Monday, November 27, 2017

See you later, Alligator See you soon , Baboon; Stay loose , Bull Moose Bye-bye, Butterfly by the Bard of Bat Yam, Poet Laureate of Zion

See you later, Alligator

See you soon , Baboon

Stay loose , Bull Moose

Bye-bye, Butterfly

Must Hit The trail , Tiny Snail

Gotta Bail , Blue Whale

Go to go , Buffalo

Chow chow, Brown Cow

Be sweet Parakeet

Bye for now , Brown Cow

Give a hug, Ladybug

In an hour , Sun flower

Maybe two, Kangeroo

Adieu , Cockatoo

Cheers , Big Ears

Till then, Penguin

Must hit the road,Happy Toad

So Long, King Kong

Adios , Hippos

In a shake, Garter Snake

Shalom , Bom Bom

Hasta manama , Iguana

Time to scoot, Little Newt

Better swish ,Jellyfish

Take care , Black Bear

In a while Crocodile

Give a kiss, Goldfish

Out the door , Dinasaur

Aloha , Iguana

Chop chop Lollipop

Get in line, Porcupine

Bye bye, Dragon Fly

Take Care, Black Bear

After a while, Crocodile

Toodle-ee-oo, Kangaroo

See you soon, Raccoon

Time to go, Buffalo

Better shake, Rattle Snake

Can’t stay, Blue Jay

Mañana, iguana

Arrivederci, Mrs Darcy

Take care, Polar Bear

This is the end, My Friend!

Thursday, November 23, 2017

Katouchka , will you sill love me when I am old ? by the Bad of Bat Yam, Poet Laureate of Zion

I would ask of you, my Katouchka ,a question ancient,soft and low,

That has given many I think a great heartache,as the epoch of seasons come and go.

Down the rivulet of life together,Katouchka, we are about to sail, side by side,

Hoping some bright day to Shomron anchor safe beyond the cascading tide.

Today our Zion sky is cloudless,butt grey nimbus clouds may unfold;

And tempest storms gather round us, Katouchka,will you still love me when I'm old?

Katouchka your love I know is veracious , but even the truest love may grow cold;

It is this that I would ask you, will you still love me when I'm old?

Life's moon will in two score year start waning, and its evening bells eventually be tolled,

But Katouchka my heart shall know no melancholy sadness,If you'll still love me when I'm old.

Kaouchka when my hair shade the white snowdrift, and mine eyes shall nebulous dimmer grow,

I would need to lean upon some loved one, through voyages of life's as I go.

I would claim of you a promise, worth to me more than ten Fort Knox of gold;

It is only this, my Katouchka ,that you'll still love me when I'm old.

It is this that I would ask you, will you still love me when I'm old?

Life's moon will in two score year start waning, and its evening bells eventually be tolled,

But Katouchka my heart shall know no melancholy sadness,If you'll still love me when I'm old.

Kaouchka when my hair shade the white snowdrift, and mine eyes shall nebulous dimmer grow,

I would need to lean upon some loved one, through voyages of life's as I go.

I would claim of you a promise, worth to me more than ten Fort Knox of gold;

It is only this, my Katouchka ,that you'll still love me when I'm old.

Wednesday, November 22, 2017

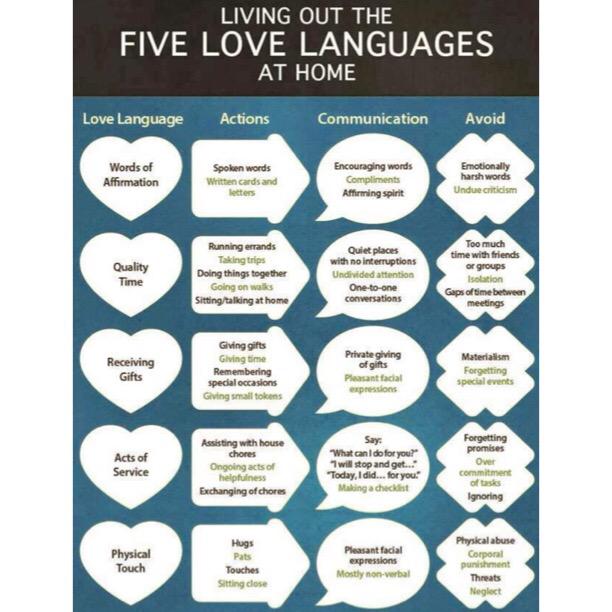

Love's Language By Ella Wheeler Wilcox... a favourite poem of the Bard of Bat Yam , Poet Laureate of Zion

Ella Wheeler Wilcox (1850 - 1919) was an American author and poet. Her best-known work was Poems of Passion. Her most enduring work was "Solitude", which contains the lines: "Laugh, and the world laughs with you; Weep, and you weep alone". Her autobiography, The Worlds and I, was published in 1918, a year before her death.

How does Love speak?

In the faint flush upon the telltale cheek,

And in the pallor that succeeds it; by

The quivering lid of an averted eye--

The smile that proves the parent to a sigh

Thus doth Love speak.

How does Love speak?

By the uneven heart-throbs, and the freak

Of bounding pulses that stand still and ache,

While new emotions, like strange barges, make

Along vein-channels their disturbing course;

Still as the dawn, and with the dawn's swift force--

Thus doth Love speak.

How does Love speak?

In the avoidance of that which we seek--

The sudden silence and reserve when near--

The eye that glistens with an unshed tear--

The joy that seems the counterpart of fear,

As the alarmed heart leaps in the breast,

And knows, and names, and greets its godlike guest--

Thus doth Love speak.

How does Love speak?

In the proud spirit suddenly grown meek--

The haughty heart grown humble; in the tender

And unnamed light that floods the world with splendor;

In the resemblance which the fond eyes trace

In all fair things to one beloved face;

In the shy touch of hands that thrill and tremble;

In looks and lips that can no more dissemble--

Thus doth Love speak.

How does Love speak?

In the wild words that uttered seem so weak

They shrink ashamed in silence; in the fire

Glance strikes with glance, swift flashing high and higher,

Like lightnings that precede the mighty storm;

In the deep, soulful stillness; in the warm,

Impassioned tide that sweeps through throbbing veins,

Between the shores of keen delights and pains;

In the embrace where madness melts in bliss,

And in the convulsive rapture of a kiss--

Thus doth Love speak.

Tuesday, November 21, 2017

Sonnet 65 by William Shakespeare... a favorite poem of the Bard of Bat Yam, Poet Laureate of Zion,

Since brass, nor stone, nor earth, nor boundless sea,

But sad mortality o’er-sways their power,

How with this rage shall beauty hold a plea

Whose action is no stronger than a flower?

O, how shall summer’s honey breath hold out

Against the wreckful siege of battering days,

When rocks impregnable are not so stout,

Nor gates of steel so strong, but Time decays?

O fearful meditation! where, alack,

Shall Time’s best jewel from Time’s chest lie hid?

Or what strong hand can hold his swift foot back?

Or who his spoil of beauty can forbid?

O, none, unless this miracle have might,

That in black ink my love may still shine bright.

Sonnet 65 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It is a member of the Fair Youth sequence, in which the poet expresses his love towards a young man.

Synopsis

This sonnet is a continuation of Sonnet 64, and is an influential poem on the aspect of Time's destruction. Shakespeare also offers an escape from Time's clasp in his end couplet, suggesting that the love and human emotion he has used through his writing will test Time and that through the years the black ink will still shine bright. Shakespeare begins this sonnet by listing several seemingly vast and unbreakable things which are destroyed by time, then asking what chance beauty has of escaping the same fate. A main theme is that many things are powerful, but nothing remains in this universe forever, especially not a fleeting emotion such as love. Mortality rules over the universe and everything is perishable in this world, so it is only through the timeless art of writing that emotion and beauty can be preserved.

Structure

Sonnet 65 is an English or Shakespearean sonnet. The English sonnet has three quatrains, followed by a final rhyming couplet. It follows the typical rhyme scheme of the form, abab cdcd efef gg and is composed in iambic pentameter, a type of poetic metre based on five pairs of metrically weak/strong syllabic positions. The first line exemplifies a regular iambic pentameter: × / × / × / × / × / Since brass, nor stone, nor earth, nor boundless sea, (65.1)

/ = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus.

The tenth line exhibits a rightward movement of the third ictus (the resulting four-position figure, × × / /, is sometimes referred to as a minor ionic): × / × / × × / / × / Shall Time's best jewel from Time's chest lie hid? (65.10)

This figure may also be detected in lines eleven and fourteen, along with an initial reversal in line three.

Analysis

Relation to adjacent sonnets

Time is not an innocuous entity. Here in Sonnet 65 Shakespeare shows time's cruel ravages on all that we believe is enduring. According to Lowry Nelson, Jr., Sonnet 65 is simply a continuation of Sonnet 64 and he argues that "both poems are meditations on the theme of time's destructiveness". He also explains that "Sonnet 65 makes use of the same words [brass, rage, hand, love] and more or less specific notions, but it proceeds and culminates far more impressively," in comparison to Sonnet 64. The last two couplets are Shakespeare's own summary on the theme that love itself is a "miracle" that time nor human intervention can destroy.

Shakespeare critic Brents Stirling expands on Lowry's idea by placing sonnet 65 in a distinct group among the sonnets presumably addressed to Shakespeare's young friend, because of the strictly third-person mode of address. Stirling links sonnets 63-68 through their use of "uniform epithet, 'my love' or its variants such as 'my beloved' ". In sonnet 65, the pronoun 'his' directly references the epithet. "Sonnet 65 opens with an epitome of [sonnet] 64: 'Since brass not stone nor earth nor boundless sea..." The opening line refers back to the 'brass,' 'lofty towers,' 'firm soil,' and 'wa'try main' of 64.] 'This rage' of 'sad mortality' calls to mind the 'mortal rage' of 64. "After its development of 64, sonnet 65 returns with its couplet to the couplet of 63: 'That in black ink my love may still shine bright' echoes 'His beauty' that 'shall in these black lines be seen'; and 'still shine' recalls 'still green' ". This "triad" of poems relates to the group of sonnets 66-68, for "Their respective themes, Time's ruin (63-65) and the Former Age, a pristine earlier world now in ruin and decay (66-68), were conventionally associated in Shakespeare's day," suggesting that the sonnets were written as a related group meant to be distinctly categorized.

Verbal patterns

Shakespearean scholar Helen Vendler characterizes Sonnet 65 as a "defective key word" sonnet. Often, Shakespeare will use a particular word prominently in each quatrain, prompting the reader to look for it in the couplet and note any change in usage. Here, however, he repeats the words "hold" and "strong" (modified slightly to "stronger" in Q1), but omits them in the couplet, thus rendering them "defective." Vendler claims that these key words are replaced by "miracle" and "black ink" respectively in the quatrain, citing as evidence the shift of focus from organic to inorganic, which parallels the same shift occurring more broadly from the octave to the sestet, as well as the presence of the letters i, a, c, and l visually yoking miracle to black ink. Stephen Booth supports this line of criticism, noting the juxtaposition of "hand" and "foot" in line 11, suggesting someone being tripped up and perhaps mirroring the shift to come in the couplet.

Barry Adams furthers the characterization of Sonnet 65 as somehow disrupted or defective, noting the usage of "O" to begin the second and third quatrains and the couplet, but not the first quatrain. He also notes the paradoxical nature of this device: "The effect of this last verbal repetition is to modify (if not nullify) the normal 4+4+4+2 structure of the English or Shakespearean sonnet by blurring the distinction between couplet and quatrain. Yet the argumentative structure of the poem insists on that distinction, since the concluding couplet is designed precisely to qualify or even contradict the observations in the first three quatrains.".

Joel Fineman treats Sonnet 65 as epideictic. He injects cynicism into the Fair Youth sonnets, claiming that the speaker does not believe fully in the immortalizing power of his verse; that it is merely literary and ultimately unreal. He treats the "still" in line 14 as wordplay, reading it to mean "dead, unmoving" rather than "perpetual, eternal".] There is some scholarly debate over this point, though. Carl Atkins, for example, writes that the reader is "not to take the couplet's 'unless' seriously. We are not expected to have any doubt that the 'miracle' of making the beloved shine brightly in black ink has might. Of course it does - we have been told so before. 'Who can hold back time?' the speaker asks. 'No one, except me,' is the answer". Philip Martin tends toward agreement with Atkins, but refutes the suggestion that the reader is "not to take the couplet's 'unless' seriously," asserting instead that, "the poem's ending is...deliberately and properly tentative". Murray Krieger agrees with Martin's point that, "the end of 65 is stronger precisely because it is so tentative". "The soft, almost non-consonantal 'how shall summer's honey breath hold out' " offers no resistance to Time's 'wrackful siege of batt'ring days'. Krieger suggests that while the sonnet does not resist Time through an assertion of strength, the concession of weakness by the placement of hope solely on a 'miracle,' offers an appeal against Time: "May there not be a strength that arises precisely from the avoidance of it?".

Connection to The Tragedy of Julius Cæsar

Time is a natural force from which none of us is immune. This theme pervades the sonnet; the speaker recognizes that time will strip the beloved of his beauty and by saying that implies that time will take his beloved from him. Eventually, time will consume everyone in death, and, whether one chooses to recognize it or not, he will not have any control over exactly when that consumption will take place. This theme translates to Julius Caesar as well. Caesar is unfazed by the soothsayer's proclamation in act one, and even though

Calpurnia seems for a time to have succeeded in keeping Caesar home on the day of his eventual murder, he goes to Senate anyway. Caesar walks into his own death, much less literally than Brutus, who does actually walk into the sword that kills him. But in these deaths in the context of the play serve to elucidate the truth that death (or 'Time', as the sonnet refers to it) will consume you regardless of your ambitions or future plans; it does not take you into consideration. Obviously, Caesar would not have gone to Senate if he knew he would be stabbed upon entering, just as Brutus and Cassius would not have engaged in a full-blown war if they knew they would be dead before it was over.

It is coincidental enough that the speaker suggests that the only way to immortalize his beloved as he is, is through his writing. And the way that Caesar and the others are kept alive is through writing, through history, and in some senses through Shakespeare himself.

It is rather universally accepted that a body of Shakespeare's sonnets, including 65, are addressed to a young man whose beauty the poems make known. The young man is like Caesar, then, in that Shakespeare recognizes the presence of feminine qualities in a man. But the common theme is more than recognition, it is an acknowledgment of tension created by that recognition. Especially by Cassius, Caesar is made out to be rather feminine, as is the young man in descriptions of his beauty. In that the speaker does not directly refer to the addressee of the sonnets as a man, and in that Brutus and the others find discomfort in Caesar's ruling ability because of his appeared weaknesses, shows that Shakespeare recognizes an anxiety about men with feminine qualities, or women with masculine qualities, like Queen Elizabeth, of whom Caesar may or may not be representative.

It is coincidental enough that the speaker suggests that the only way to immortalize his beloved as he is, is through his writing. And the way that Caesar and the others are kept alive is through writing, through history, and in some senses through Shakespeare himself.

It is rather universally accepted that a body of Shakespeare's sonnets, including 65, are addressed to a young man whose beauty the poems make known. The young man is like Caesar, then, in that Shakespeare recognizes the presence of feminine qualities in a man. But the common theme is more than recognition, it is an acknowledgment of tension created by that recognition. Especially by Cassius, Caesar is made out to be rather feminine, as is the young man in descriptions of his beauty. In that the speaker does not directly refer to the addressee of the sonnets as a man, and in that Brutus and the others find discomfort in Caesar's ruling ability because of his appeared weaknesses, shows that Shakespeare recognizes an anxiety about men with feminine qualities, or women with masculine qualities, like Queen Elizabeth, of whom Caesar may or may not be representative.

Saturday, November 18, 2017

Good Morning ,Katy, Good Morning

Every day brings so much more

To look forward to ,fly high and soar

Every moment brings so much delight

Just being with you,makes everything feel right

Good morning ,Katy Good Morning

Thursday, November 9, 2017

There was a lovely lady from Karnei Shomron

There was a lovely lady from Karnei Shomron

Who at 9am chatted up her future Romeo with amorous wanton

She was bold as she was beautiful and very willing

She pondered looking at her computer screen and not the ceiling.

And wondered when they would first,with kisses and cuddles, meet in Tziyon

- noun: lascivious woman

- verb: spend wastefully

- verb: engage in amorous play

- verb: waste time; spend one's time idly or inefficiently

- verb: become extravagant; indulge (oneself) luxuriously

- adjective: occurring without motivation or provocation

- adjective: casual and unrestrained in sexual behavior

( You owe me two hugs and three kisses for a new word xoxoxox )

Sunday, October 15, 2017

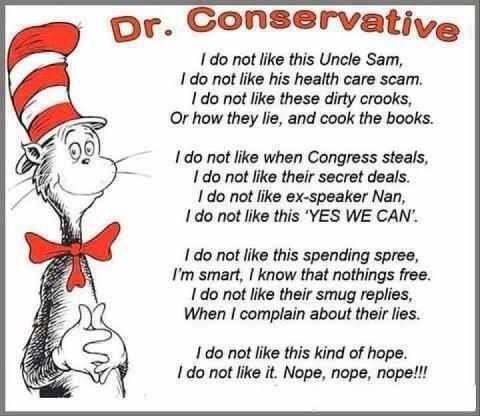

Dr Seuss on Big Boobs and Lips by the Bard of Bat Yam, Poet Laureate of Zion

Percy Bysshe Shelley: “Ozymandias” A poem to outlast empires. by the Bard of Bat Yam, Poet Laureate of Zion

I met a traveller from an antique land

Who said: “Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert . . . Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed:

And on the pedestal these words appear:

‘My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!'

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

Shelley’s friend the banker Horace Smith stayed with the poet and his wife Mary (author of Frankenstein) in the Christmas season of 1817. One evening, they began to discuss recent discoveries in the Near East. In the wake of Napoleon’s conquest of Egypt in 1798, the archeological treasures found there stimulated the European imagination. The power of pharaonic Egypt had seemed eternal, but now this once-great empire was (and had long been) in ruins, a feeble shadow.Shelley and Smith remembered the Roman-era historian Diodorus Siculus, who described a statue of Ozymandias, more commonly known as Rameses II (possibly the pharaoh referred to in the Book of Exodus). Diodorus reports the inscription on the statue, which he claims was the largest in Egypt, as follows: “King of Kings Ozymandias am I. If any want to know how great I am and where I lie, let him outdo me in my work.” (The statue and its inscription do not survive, and were not seen by Shelley; his inspiration for “Ozymandias” was verbal rather than visual.)

Stimulated by their conversation, Smith and Shelley wrote sonnets based on the passage in Diodorus. Smith produced a now-forgotten poem with the unfortunate title “On a Stupendous Leg of Granite, Discovered Standing by Itself in the Deserts of Egypt, with the Inscription Inserted Below.” Shelley’s contribution was “Ozymandias,” one of the best-known sonnets in European literature.

In addition to the Diodorus passage, Shelley must have recalled similar examples of boastfulness in the epitaphic tradition. In the Greek Anthology (8.177), for example, a gigantic tomb on a high cliff proudly insists that it is the eighth wonder of the world. Here, as in the case of “Ozymandias,” the inert fact of the monument displaces the presence of the dead person it commemorates: the proud claim is made on behalf of art (the tomb and its creator), not the deceased. Though Ozymandias believes he speaks for himself, in Shelley’s poem his monument testifies against him.

“Ozymandias” has an elusive, sidelong approach to its subject. The poem begins with the word “I”—but the first person here is a mere framing device. The “I” quickly fades away in favor of a mysterious “traveler from an antique land.” This wayfarer presents the remaining thirteen lines of the poem.

The reader encounters Shelley’s poem like an explorer coming upon a strange, desolate landscape. The first image that we see is the “two vast and trunkless legs of stone” in the middle of a desert. Column-like legs but no torso: the center of this great figure, whoever he may have been, remains missing. The sonnet comes to a halt in the middle of its first quatrain. Are these fragmentary legs all that is left?

After this pause, Shelley’s poem describes a “shattered visage,” the enormous face of Ozymandias. The visage is taken apart by the poet, who collaborates with time’s ruinous force. Shelley says nothing about the rest of the face; he describes only the mouth, with its “frown,/And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command.” Cold command is the emblem of the empire-building ruler, of the tyrannical kind that Shelley despised. Ozymandias resembles the monstrous George III of our other Shelley sonnet, “England in 1819.” (Surprisingly, surviving statues of Rameses II, aka Ozymandias, show him with a mild, slightly mischievous expression, not a glowering, imperious one.)

The second quatrain shifts to another mediating figure, now not the traveler but the sculptor who depicted the pharaoh. The sculptor “well those passions read,” Shelley tells us: he intuited, beneath the cold, commanding exterior, the tyrant’s passionate rage to impose himself on the world. Ozymandias’ intense emotions “survive, stamp’d on these lifeless things.” But as Shelley attests, the sculptor survives as well, or parts of him do: “the hand that mocked” the king’s passions “and the heart that fed.” (The artist, like the tyrant, lies in fragments.) “Mocked” here has the neutral sense of “described” (common in Shakespeare), as well as its more familiar meaning, to imitate in an insulting way. The artist mocked Ozymandias by depicting him, and in a way that the ruler could not himself perceive (presumably he was satisfied with his portrait). “The heart that fed” is an odd, slightly lurid phrase, apparently referring to the sculptor’s own fervent way of nourishing himself on his massive project. The sculptor’s attitude might resemble—at any event, it certainly suits—the pharaoh’s own aggressive enjoyment of empire. Ruler and artist seem strangely linked here; the latter’s contempt for his subject does not free him from Ozymandias’ enormous shadow.

The challenge for Shelley will thus be to separate himself from the sculptor’s harsh satire, which is too intimately tied to the power it opposes. If the artistic rebel merely plays Prometheus to Ozymandias’ Zeus, the two will remain locked in futile struggle (the subject of Shelley’s great verse drama Prometheus Unbound). Shelley’s final lines, with their picture of the surrounding desert, are his attempt to remove himself from both the king and the sculptor—to assert an uncanny, ironic perspective, superior to the battle between ruler and ruled that contaminates both.

The sestet moves from the shattered statue of Ozymandias to the pedestal, with its now-ironic inscription: “‘My name is Ozymandias, king of kings./Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair!’” Of course, the pharaoh’s “works” are nowhere to be seen, in this desert wasteland. The kings that he challenges with the evidence of his superiority are the rival rulers of the nations he has enslaved, perhaps the Israelites and Canaanites known from the biblical account. The son and successor of Ozymandias/Rameses II, known as Merneptah, boasts in a thirteenth-century BCE inscription (on the “Merneptah stele,” discovered in 1896 and therefore unknown to Shelley) that “Israel is destroyed; its seed is gone”—an evidently overoptimistic assessment.

The pedestal stands in the middle of a vast expanse. Shelley applies two alliterative phrases to this desert, “boundless and bare” and “lone and level.” The seemingly infinite empty space provides an appropriate comment on Ozymandias’ political will, which has no content except the blind desire to assert his name and kingly reputation.

“Ozymandias” is comparable to another signature poem by a great Romantic, Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s “Kubla Khan.” But whereas Coleridge aligns the ruler’s “stately pleasure dome” with poetic vision, Shelley opposes the statue and its boast to his own powerful negative imagination. Time renders fame hollow: it counterposes to the ruler’s proud sentence a devastated vista, the trackless sands of Egypt.

Ozymandias and his sculptor bear a fascinating relation to Shelley himself: they might be seen as warnings concerning the aggressive character of human action (whether the king’s or the artist’s). Shelley was a ceaselessly energetic, desirous creator of poetry, but he yearned for calm. This yearning dictated that he reach beyond his own willful, anarchic spirit, beyond the hubris of the revolutionary. In his essay “On Life,” Shelley writes that man has “a spirit within him at enmity with dissolution and nothingness.” In one way or another, we all rebel against the oblivion to which death finally condemns us. But we face, in that rebellion, a clear choice of pathways: the road of the ardent man of power who wrecks all before him, and is wrecked in turn; or the road of the poet, who makes his own soul the lyre or Aeolian harp for unseen forces. (One may well doubt the strict binary that Shelley implies, and point to other possibilities.) Shelley’s limpid late lyric “With a Guitar, to Jane” evokes wafting harmonies and a supremely light touch. This music occupies the opposite end of the spectrum from Ozymandias’ futile, resounding proclamation. Similarly, in the “Ode to the West Wind,” Shelley’s lyre opens up the source of a luminous vision: the poet identifies himself with the work of song, the wind that carries inspiration. The poet yields to a strong, invisible power as the politician cannot.

In a letter written during the poet’s affair with Jane Williams, Shelley declares, “Jane brings her guitar, and if the past and the future could be obliterated, the present would content me so well that I could say with Faust to the passing moment, ‘Remain, thou, thou art so beautiful.’” The endless sands of “Ozymandias” palpably represent the threatening expanse of past and future. Shelley’s poem rises from the desert wastes: it entrances us every time we read it, and turns the reading into a “now.”

The critic Leslie Brisman remarks on “the way the timelessness of metaphor escapes the limits of experience” in Shelley. Timelessness can be achieved only by the poet’s words, not by the ruler’s will to dominate. The fallen titan Ozymandias becomes an occasion for Shelley’s exercise of this most tenuous yet persisting form, poetry. Shelley’s sonnet, a brief epitome of poetic thinking, has outlasted empires: it has witnessed the deaths of boastful tyrants, and the decline of the British dominion he so heartily scorned.

Saturday, October 14, 2017

Facebook By Dr Seuss by the Bard of Bat Yam, Poet Laureate of Zion

The Conservative by the Bard of Bat Yam, Poet Laureate of Zion

Dr Seuss Does Facebook by the Bard of Bat Yam, Poet Laureate of Zion

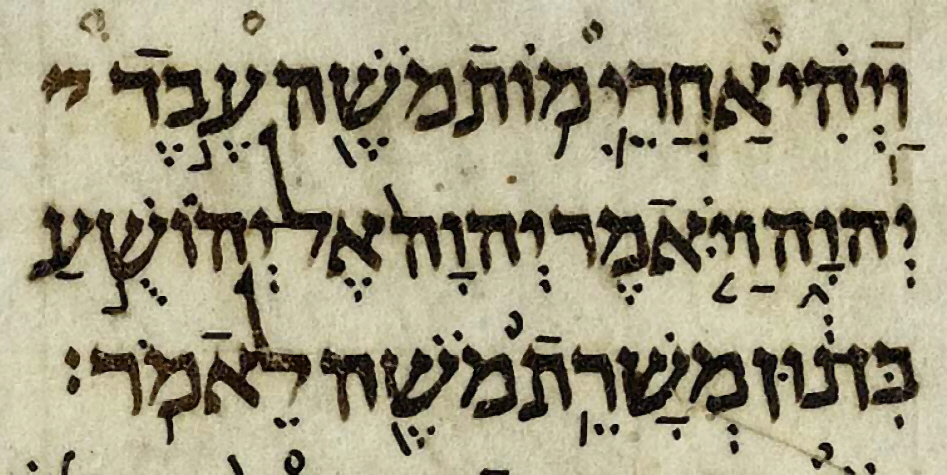

Think how the meters of a distant tongue Gave figuration to men’s hopes and fears, by the Bard of Bat Yam , Poet Laureate of Zion

Think how the meters of a distant tongue

Gave figuration to men’s hopes and fears,

To passions gravity, to love its tears,

The chords with which our human hearts are strung.

Gave figuration to men’s hopes and fears,

To passions gravity, to love its tears,

The chords with which our human hearts are strung.

Consider how the bards of old had sung

Before their numbers vanished with the years,

And how their harps delighted captive ears

When thought itself was green and fancy young.

Before their numbers vanished with the years,

And how their harps delighted captive ears

When thought itself was green and fancy young.

Alas, my song cannot unburthen care

Nor life’s unceasing worriments remove;

And though my lays be lost on empty air,

Nor life’s unceasing worriments remove;

And though my lays be lost on empty air,

Yet, days to come shall not these notes reprove:

Their sweetness imitates a single fair,

The music that is you, my only love.

Their sweetness imitates a single fair,

The music that is you, my only love.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)