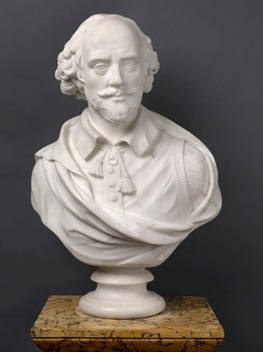

William Shakespeare (baptized April 26, 1564 – died April 23, 1616) is arguably the greatest writer in any language. His poetry is not only one of the most exalted examples of what an immortal sense of creative identity can accomplish, but it is in a sense a kind of symbol for the immortality of the artist and the idea of timelessness itself. From this standpoint, the idea of classical poetry and classical culture was never to be understood as something based “in time,” as if from a certain period, but rather, it was considered classical because of the nature of the ideas it advanced, ideas which the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley referred to as “profound ideas concerning man and nature”; it was classical because of the way in which it chose to represent these ideas, namely, through beauty. Every great culture which has had the opportunity to fully develop its potential has likely had a “classical” period. In a word: a work assumes the title of classical, of a “classic,” because of the quality of soul which emanates from it; it says something about the human condition in ways which make it stand as if outside of time and space – it is a “classic”.

In this context, while there are myriad websites listing Shakespeare’s top 10 sonnets, and no two lists are likely to be the same, the relevant issue in defining 10 of Shakespeare’s greatest sonnets is that of selecting those which give us a glimpse into the higher order of meaning weaved through the series of sonnets as a whole; it means selecting those sonnets which capture the depths of Shakespeare’s insight into the nature of man. It also means considering what is often overlooked by the more “popular” or academic readings of Shakespeare.

Too often Shakespeare readings are weighed down by an overly romanticized or sentimental reading, focusing on the sonnets as solely isolated pieces dedicated to the infatuation with some literal subject. What happens is one fails to see what Shakespeare is actually trying to accomplish. We are of the opinion that no such top 10 list could be compiled, which does not take into account or recognize the higher order of meaning, which governs the totality of the series – just as the star, which governs the orbits of all its planets and moons. In this light, we have attempted to select 10 of Shakespeare’s greatest sonnets.

10. Sonnet #1

From fairest creatures we desire increase,

That thereby beauty’s rose might never die,

But as the riper should by time decease,

His tender heir might bear his memory:

But thou contracted to thine own bright eyes,

Feed’st thy light’s flame with self-substantial fuel,

Making a famine where abundance lies,

Thy self thy foe, to thy sweet self too cruel:

Thou that art now the world’s fresh ornament,

And only herald to the gaudy spring,

Within thine own bud buriest thy content,

And, tender churl, mak’st waste in niggarding:

Pity the world, or else this glutton be,

To eat the world’s due, by the grave and thee.

That thereby beauty’s rose might never die,

But as the riper should by time decease,

His tender heir might bear his memory:

But thou contracted to thine own bright eyes,

Feed’st thy light’s flame with self-substantial fuel,

Making a famine where abundance lies,

Thy self thy foe, to thy sweet self too cruel:

Thou that art now the world’s fresh ornament,

And only herald to the gaudy spring,

Within thine own bud buriest thy content,

And, tender churl, mak’st waste in niggarding:

Pity the world, or else this glutton be,

To eat the world’s due, by the grave and thee.

Some might suggest Shakespeare’s idea of beauty is only skin deep, but right from the first two lines it’s stated that this beauty fades and that even the fairest of creature’s is no match for Time. He says we are all attracted to beauty and long for it, “from fairest creatures” we desire ‘increase,’ i.e. to reproduce, yet in recognizing that this kind of beauty fades, Shakespeare prepares you to discover an even higher order of beauty: the power to create new beauty! Herein lies the germ of Shakespeare’s entire theme as he develops it throughout the series. However, he warns us and the ostensible person he is addressing, that to be preoccupied with one’s own beauty, is to be blind to this qualitatively higher order of beauty, which lies in the future.

Thus right from the beginning we are faced with the question of our mortality and the contemplation of what comes after us. Shakespeare begins with this question because he knows that it is the only way in which we can be brought to contemplating a higher level of idea: our immortality.

9. Sonnet #130

My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun;

Coral is far more red, than her lips red:

If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun;

If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head.

I have seen roses damasked, red and white,

But no such roses see I in her cheeks;

And in some perfumes is there more delight

Than in the breath that from my mistress reeks.

I love to hear her speak, yet well I know

That music hath a far more pleasing sound:

I grant I never saw a goddess go,

My mistress, when she walks, treads on the ground:

And yet by heaven, I think my love as rare,

As any she belied with false compare.

Coral is far more red, than her lips red:

If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun;

If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head.

I have seen roses damasked, red and white,

But no such roses see I in her cheeks;

And in some perfumes is there more delight

Than in the breath that from my mistress reeks.

I love to hear her speak, yet well I know

That music hath a far more pleasing sound:

I grant I never saw a goddess go,

My mistress, when she walks, treads on the ground:

And yet by heaven, I think my love as rare,

As any she belied with false compare.

It was very popular to use all sorts of exaggerated comparisons to define one’s love, whether it be with the sweetness of a summer day, to the softness of the winds, with the brightness of the sun, ultimately always only using this as a device by which to declare their love surpasses all such comparison. By turning it on its head, Shakespeare develops a metaphor which allows us to contemplate a completely different quality of beauty, one which goes beyond simple sense perception. Shakespeare is going beyond the tendency of many of the Romantic poets who would simply be content with titillating our senses and reveling in a thousand pretty images of the beloved – his love is located in something higher.

How might this higher quality be attained?

8. Sonnet #17

The creation of beauty, as opposed to one’s obsession with one’s own beauty as some fixed thing, becomes a self-developing process – it becomes the higher hypothesis of our existence. This theme is thoroughly developed from sonnets 1-16, but now in sonnet 17 (closely related to sonnet 16), something begins to happen – there is a singularity or what we might call a discontinuity in mathematical terms, in regards to the hypothesis that came before:

Who will believe my verse in time to come,

If it were filled with your most high deserts?

Though yet heaven knows it is but as a tomb

Which hides your life, and shows not half your parts.

If I could write the beauty of your eyes,

And in fresh numbers number all your graces,

The age to come would say ‘This poet lies;

Such heavenly touches ne’er touched earthly faces.’

So should my papers, yellowed with their age,

Be scorned, like old men of less truth than tongue,

And your true rights be termed a poet’s rage

And stretched metre of an antique song:

But were some child of yours alive that time,

You should live twice, in it, and in my rhyme.

If it were filled with your most high deserts?

Though yet heaven knows it is but as a tomb

Which hides your life, and shows not half your parts.

If I could write the beauty of your eyes,

And in fresh numbers number all your graces,

The age to come would say ‘This poet lies;

Such heavenly touches ne’er touched earthly faces.’

So should my papers, yellowed with their age,

Be scorned, like old men of less truth than tongue,

And your true rights be termed a poet’s rage

And stretched metre of an antique song:

But were some child of yours alive that time,

You should live twice, in it, and in my rhyme.

Shakespeare has been elaborating his concept of beauty through poetry and now begins to allude to his conception of explicitly capturing it in his verse. However he casts doubt on whether he has the ability to keep their beauty alive through verse alone and thus urges them to take fate into their own hands. Despite procreation, he fears that beauty may still not survive, or that he wishes he could better protect it against Time, an idea also present in Sonnet 16:

But wherefore do not you a mightier way

Make war upon this bloody tyrant, Time?

And fortify your self in your decay

With means more blessed than my barren rhyme?

Now stand you on the top of happy hours,

And many maiden gardens, yet unset,

With virtuous wish would bear you living flowers,

Much liker than your painted counterfeit:

So should the lines of life that life repair,

Which this, Time’s pencil, or my pupil pen,

Neither in inward worth nor outward fair,

Can make you live your self in eyes of men.

To give away yourself, keeps yourself still,

And you must live, drawn by your own sweet skill.

Make war upon this bloody tyrant, Time?

And fortify your self in your decay

With means more blessed than my barren rhyme?

Now stand you on the top of happy hours,

And many maiden gardens, yet unset,

With virtuous wish would bear you living flowers,

Much liker than your painted counterfeit:

So should the lines of life that life repair,

Which this, Time’s pencil, or my pupil pen,

Neither in inward worth nor outward fair,

Can make you live your self in eyes of men.

To give away yourself, keeps yourself still,

And you must live, drawn by your own sweet skill.

Thus Shakespeare introduces a new element into the process of generating beauty, saying “But were some child of yours alive that time / You should live twice, in it, and in my rhyme.” We are now witnessing a doubly connected hypothesis, where the creation of beauty becomes twofold. There is another level he is defining here, a higher level of cardinality, where art itself can play a role.

We will come back to the sonnets following this one later in the list.

7. Sonnet 116

Let me not to the marriage of true minds

Admit impediments. Love is not love

Which alters when it alteration finds,

Or bends with the remover to remove:

O, no! it is an ever-fixed mark,

That looks on tempests and is never shaken;

It is the star to every wandering bark,

Whose worth’s unknown, although his height be taken.

Love’s not Time’s fool, though rosy lips and cheeks

Within his bending sickle’s compass come;

Love alters not with his brief hours and weeks,

But bears it out even to the edge of doom.

If this be error and upon me proved,

I never writ, nor no man ever loved.

Admit impediments. Love is not love

Which alters when it alteration finds,

Or bends with the remover to remove:

O, no! it is an ever-fixed mark,

That looks on tempests and is never shaken;

It is the star to every wandering bark,

Whose worth’s unknown, although his height be taken.

Love’s not Time’s fool, though rosy lips and cheeks

Within his bending sickle’s compass come;

Love alters not with his brief hours and weeks,

But bears it out even to the edge of doom.

If this be error and upon me proved,

I never writ, nor no man ever loved.

In many of the popular readings of Shakespeare, there is a tendency to get lost in some of the romantic characteristics. However beautiful and pleasing, Shakespeare’s sense of subtly and layered meaning was usually used to allude to more than a simple romantic or pretty theme which makes happy lovers sigh. Despite that, Sonnet 116 is a true emblem of the marriage vow, often being recited at weddings and used as the quintessential declaration of true love. In it, Shakespeare develops the idea of love as something that transcends time and space. Man and woman, through love, assume a kind of strength which is unvanquishable and can in a certain way overcome all elements. Love in this sense partakes in the eternal, the one, and so through Love, we also may participate in this eternal, this one. Like Shakespeare says: “Love’s not Time’s fool, though rosy lips and cheeks / Within his bending sickle’s compass come.” However, Shakespeare starts the sonnet by saying something rather peculiar for the discerning eye, whose significance becomes much clearer in a proper recitation where one is challenged to communicate the intent of the first two lines: “Let me not to the marriage of true minds / Admit impediments.” Why would he be an impediment to the marriage of true minds? Which minds is he referring to?

Sonnet 116 is too often read without regard for what came before it, or what comes after it with the “dark lady” sonnets. While there are some who would insist that it doesn’t matter, and that one should just enjoy the sonnet alone, without having to know all the auxiliary circumstances and meanings, in this case, with the advent of some relatively new scholarship which brings to light the identity of the dark lady Shakespeare was writing about, it makes this sonnet 116 all the more powerful, real, and gives it a real sense of biting irony.

Hildegard Hammerschmidt-Hummel, a German Shakespeare scholar who has been known for an exceptionally scrupulous rigor in her scholarly work, bringing together elements of literary scholarship, iconography, forensic sciences, along with the use of botanical and medical expertise, put forward the hypothesis that this dark lady is none other than Elizabeth Vernon, the wife of Henry Wriothesley, the Earl of Southampton. Only ten weeks after they were married, Elizabeth gave birth to a girl.

Hammerschmidt-Hummel goes through some rather compelling evidence, using portraits from that time, including a famous one known as “The Persian Lady,” along with a previously lost sonnet (which she claims is the last and final sonnet in Shakespeare’s series) and inscriptions from the portrait. In terms of all the possible people Shakespeare might have been addressing (including Shakespeare’s connection to the Earl of Southampton), she concludes that this child was most likely Shakespeare’s son. It would also explain certain intrigues around that time. It is not our purpose to try and convince people of these findings. That being said, availing ourselves of such a hypothesis in order to situate the context of this later series and account for the irony at the beginning of Sonnet 116, proves to be surprisingly useful. It becomes helpful in aiding one picture the possibilities and scenarios which speak to the kinds of sub-narratives Shakespeare explicitly refers to throughout many of the sonnets in the series. Moreover, it also gives meaning to the two opening lines, which we’re otherwise forced to believe are just some superfluous rhetorical device which otherwise have nothing to do with the content of the sonnet. In the case the hypothesis is relatively correct, then Sonnet 116 becomes a formidable example of that biting irony which is so characteristic of the bard.

We recommend the reader at least give the sonnet a genuine reading aloud and try to play around with the different possibilities involved in its recitation. In this light, it becomes interesting to follow this sonnet up with these lines from Sonnet 117:

Book both my wilfulness and errors down,

And on just proof surmise accumulate;

Bring me within the level of your frown,

But shoot not at me in your wakened hate;

Since my appeal says I did strive to prove

The constancy and virtue of your love.

And on just proof surmise accumulate;

Bring me within the level of your frown,

But shoot not at me in your wakened hate;

Since my appeal says I did strive to prove

The constancy and virtue of your love.

6. Sonnet #129

Here we have a denunciation of lust, its effects, in the midst of developing the theme of the “dark lady,” warning us:

The expense of spirit in a waste of shame

Is lust in action: and till action, lust

Is perjured, murderous, bloody, full of blame,

Savage, extreme, rude, cruel, not to trust;

Enjoyed no sooner but despised straight;

Past reason hunted; and no sooner had,

Past reason hated, as a swallowed bait,

On purpose laid to make the taker mad.

Mad in pursuit and in possession so;

Had, having, and in quest to have extreme;

A bliss in proof, and proved, a very woe;

Before, a joy proposed; behind a dream.

All this the world well knows; yet none knows well

To shun the heaven that leads men to this hell.

Is lust in action: and till action, lust

Is perjured, murderous, bloody, full of blame,

Savage, extreme, rude, cruel, not to trust;

Enjoyed no sooner but despised straight;

Past reason hunted; and no sooner had,

Past reason hated, as a swallowed bait,

On purpose laid to make the taker mad.

Mad in pursuit and in possession so;

Had, having, and in quest to have extreme;

A bliss in proof, and proved, a very woe;

Before, a joy proposed; behind a dream.

All this the world well knows; yet none knows well

To shun the heaven that leads men to this hell.

Shakespeare is reflecting on the conflicting battle of one’s infatuation with a beautiful thing, the feeling of being enthralled to it, and the strong desire to “possess” it as though it were some object, some “thing” we wish to claim. The woman he loved, has yet chosen another course for her life it seems, but he cannot seem to let go (whether the Elizabeth Vernon narrative be entirely accurate or not); he is conflicted with the different feelings of desire, fear, loss. He is sharing all this with us, he is an open book, and in saying all this he is warning the reader to look beyond their immediate feelings, their impulses, no matter how noble they may seem – do not be so blind as to not recognize “the heaven that leads men to Hell.”

Thus the struggle with sense perception, and of overcoming even the greatest sense of power which our unbridled feelings might have, leads us to the contemplation of mind and its role in our true happiness. Whether the narrative of Elizabeth Vernon is fully correct or not, is in this case secondary to understanding the sonnet in its context, however it does help to serve as a kind of predicate, or device by which to imagine the sort of circumstances under which this kind of series of hypothesis and of conflicting emotions might have arisen. It also helps to humanize Shakespeare, and helps us to not be so vain as to imagine some great individual above all human folly and error.

In our estimation, it is not diminutive to speculate on these kinds of issues about Shakespeare, it is all the more powerful to consider that such a human being, who struggled with many of the complexities of life which all our fellow human beings struggle with, was yet able to overcome himself, through his commitment to creativity, and ascend to the awesome heights of the immortal bard. This series is the record of his journey.

See sonnets 147-150 for a full depiction of the battle between sense and mind, between the commitment to truth and love, and the deceptions of lust and ego –

“Oh me, what eyes hath Love put in my head

Which have no correspondence with true sight!” (Sonnet 148)

Which have no correspondence with true sight!” (Sonnet 148)

5. Sonnet #55

Not marble, nor the gilded monuments

Of princes, shall outlive this powerful rhyme;

But you shall shine more bright in these contents

Than unswept stone, besmear’d with sluttish time.

When wasteful war shall statues overturn,

And broils root out the work of masonry,

Nor Mars his sword, nor war’s quick fire shall burn

The living record of your memory.

‘Gainst death, and all oblivious enmity

Shall you pace forth; your praise shall still find room

Even in the eyes of all posterity

That wear this world out to the ending doom.

So, till the judgment that yourself arise,

You live in this, and dwell in lovers’ eyes.

Of princes, shall outlive this powerful rhyme;

But you shall shine more bright in these contents

Than unswept stone, besmear’d with sluttish time.

When wasteful war shall statues overturn,

And broils root out the work of masonry,

Nor Mars his sword, nor war’s quick fire shall burn

The living record of your memory.

‘Gainst death, and all oblivious enmity

Shall you pace forth; your praise shall still find room

Even in the eyes of all posterity

That wear this world out to the ending doom.

So, till the judgment that yourself arise,

You live in this, and dwell in lovers’ eyes.

In Sonnet 55 Shakespeare asserts the primacy of his poetic power, as that force, which defies the elements – that which is immortal. In the context of epic historical changes, of harrowing battles and of the crashing down of monuments, through a sweeping depiction of the vicissitudes of life, despite this, Shakespeare’s rhyme partakes of something higher, which these monuments, these stones, these princes cannot, because they do not possess creativity.

Of all the subjects he chooses to write about, he chooses love, and as a show of his love, his rhyme becomes the vehicle by which to immortalize it. On a higher level, this also demonstrates the power of love itself, of Agape, of selfless love, and of love for mankind, which is that force which moves one to create that which overcomes all worldly obstacles.

4. Sonnet #18

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate:

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer’s lease hath all too short a date:

Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines,

And often is his gold complexion dimmed,

And every fair from fair sometime declines,

By chance, or nature’s changing course untrimmed:

But thy eternal summer shall not fade,

Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow’st,

Nor shall death brag thou wander’st in his shade,

When in eternal lines to time thou grow’st,

So long as men can breathe, or eyes can see,

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

Thou art more lovely and more temperate:

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer’s lease hath all too short a date:

Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines,

And often is his gold complexion dimmed,

And every fair from fair sometime declines,

By chance, or nature’s changing course untrimmed:

But thy eternal summer shall not fade,

Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow’st,

Nor shall death brag thou wander’st in his shade,

When in eternal lines to time thou grow’st,

So long as men can breathe, or eyes can see,

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

Arguably the most famous of the Shakespeare sonnets, and definitely one of the most beautiful, Shakespeare uses the device of making a series of comparisons, which shows up in its inverted form in Sonnet 130, in order to show how his Love yet surpasses any idea of comparison. In that sense, the only way to go beyond, is to write that which exceeds all these notions of beauty, whereby, through his art, which captures what nothing else can, he immortalizes his love. Because of the tenderness and ideality of this particular sonnet, its use of such delicate images to convey this great sense of beauty, we are compelled to say it is truly one of the most beautiful.

3. Sonnet #59

If there be nothing new, but that which is

Hath been before, how are our brains beguil’d,

Which labouring for invention bear amiss

The second burthen of a former child.

Oh that record could with a backward look,

Even of five hundred courses of the sun,

Show me your image in some antique book,

Since mind at first in character was done,

That I might see what the old world could say

To this composed wonder of your frame;

Whether we are mended, or where better they,

Or whether revolution be the same.

Oh sure I am the wits of former days,

To subjects worse have given admiring praise.

Hath been before, how are our brains beguil’d,

Which labouring for invention bear amiss

The second burthen of a former child.

Oh that record could with a backward look,

Even of five hundred courses of the sun,

Show me your image in some antique book,

Since mind at first in character was done,

That I might see what the old world could say

To this composed wonder of your frame;

Whether we are mended, or where better they,

Or whether revolution be the same.

Oh sure I am the wits of former days,

To subjects worse have given admiring praise.

Shakespeare here contemplates, how do we know something as beautiful as his love has not already been written? He alludes to the biblical reference right from the beginning “there is no new thing under the sun” (Eclesiastes 1.9), creating a sort of crisis. Is what he is attempting to do all in vain? If only he could somehow go into the past and see, and “prove” his is different and that his special. Yet he concludes, as an artist, who’s nature is to create, who is in a very real sense a “co-creator”: “Oh sure I am the wits of former days / To subjects worse have given admiring praise.”

Shakespeare stands at the point of a new Renaissance, he stands in the shadow of the ancient Greek renaissance, and in the shadow of the Italian Golden Renaissance, whose sonetto form he has adopted and fitted to the English language. He has borrowed the sonetto form in order to communicate a new paradigm of “profound ideas concerning man and nature.” However, like many of the sonnets, they often come in pairs, like pairwise electrons or diatomic molecules, and here 59 is one which serves to set up the next one:

2. Sonnet #60

Like as the waves make towards the pebbled shore,

So do our minutes hasten to their end;

Each changing place with that which goes before,

In sequent toil all forwards do contend.

Nativity, once in the main of light,

Crawls to maturity, wherewith being crown’d,

Crooked eclipses ‘gainst his glory fight,

And Time that gave doth now his gift confound.

Time doth transfix the flourish set on youth

And delves the parallels in beauty’s brow,

Feeds on the rarities of nature’s truth,

And nothing stands but for his scythe to mow:

And yet to times in hope, my verse shall stand

Praising thy worth, despite his cruel hand.

So do our minutes hasten to their end;

Each changing place with that which goes before,

In sequent toil all forwards do contend.

Nativity, once in the main of light,

Crawls to maturity, wherewith being crown’d,

Crooked eclipses ‘gainst his glory fight,

And Time that gave doth now his gift confound.

Time doth transfix the flourish set on youth

And delves the parallels in beauty’s brow,

Feeds on the rarities of nature’s truth,

And nothing stands but for his scythe to mow:

And yet to times in hope, my verse shall stand

Praising thy worth, despite his cruel hand.

Shakespeare here asserts the primacy of the artist, of the creative mind, and his ability to create something “new under the sun.” This becomes fundamental for recognizing Shakespeare’s acknowledgement of where he is in history, that despite 500 courses of the sun, he is creating something new. Moreover, not only is he creating something new, but he is actually redefining the directionality of clock time, where rather than fade with the passing of time, in times to come, his “verse shall stand / Praising thy worth, despite his cruel hand.” In fact, his verse will not only stand, it will increase in greatness: rather than wear his rhyme out, each 500 new courses of the sun will increase its worth, by 500 courses of the sun. Thus Time increases its worth! This concept defines the true nature of immortality, which every individual human being may partake in.

1. Sonnet #65

Since brass, nor stone, nor earth, nor boundless sea,

But sad mortality o’ersways their power,

How with this rage shall beauty hold a plea,

Whose action is no stronger than a flower?

O! how shall summer’s honey breath hold out,

Against the wrackful siege of battering days,

When rocks impregnable are not so stout,

Nor gates of steel so strong but Time decays?

O fearful meditation! where, alack,

Shall Time’s best jewel from Time’s chest lie hid?

Or what strong hand can hold his swift foot back?

Or who his spoil of beauty can forbid?

O! none, unless this miracle have might,

That in black ink my love may still shine bright.

But sad mortality o’ersways their power,

How with this rage shall beauty hold a plea,

Whose action is no stronger than a flower?

O! how shall summer’s honey breath hold out,

Against the wrackful siege of battering days,

When rocks impregnable are not so stout,

Nor gates of steel so strong but Time decays?

O fearful meditation! where, alack,

Shall Time’s best jewel from Time’s chest lie hid?

Or what strong hand can hold his swift foot back?

Or who his spoil of beauty can forbid?

O! none, unless this miracle have might,

That in black ink my love may still shine bright.

Here the balance of historical time, of clock time, is counterposed with the most delicate images: how can such things hold a plea, when even the greatest of monuments must yield to Time? This is the question every mortal must ask in contemplating the purpose of their lives.

In this sonnet, along with Sonnet 18, one see’s how the most fragile images, those most vulnerable to the indiscriminate blows of fate and nature, have ironically, the ability to move us in the most powerful of ways, because they have the ability to invoke in us the greatest sense of humanity. In having gone through a series of hypotheses, from physical beauty, the belief in sense perceptions, the trappings of lust and the gluttony of Time; having considered the crashing down of monuments, the fortunes of princes, one’s legacy carried on by their offspring, the vicissitudes of mortality and our desires for all those things which must ultimately flee, we are yet compelled to ask: “how shall beauty hold a plea?” This becomes the most important question; by what great agency, by what saving grace, by what miracle, can Time be overcome:

O! none, unless this miracle have might,

That in black ink my love may still shine bright.

That in black ink my love may still shine bright.

The power of Love and creativity combined, are the force, which can in a very real sense move mountains, and have the power to accomplish that which seems impossible. Were Shakespeare just another skilled versifier, moved by nothing other than his wish to titillate our senses and relish in a thousand beautiful images of his beloved, his poetry would have none of the power it has today. The reason for this is simple:

Though I speak with the tongues of men and of angels, and have not charity, I am become as sounding brass, or a tinkling cymbal. -1st Corinthians 13

Shakespeare understood this in its most profound sense.

Conclusion

Shakespeare’s work is not some sentimental romanticizing of his love; nor is it really a love of an individual in the strict sense of the word; just as Petrarch’s Laura (meaning laurel in Italian) and Dante’s Beatrice, they are archetypes, predicates, by which to elaborate a qualitatively higher conception of love which is truly universal i.e. Agapic. Though this love can be expressed towards another individual, the difference is Shakespeare is not coming from a place of Eros, of wanting to possess such a love, in fact he’s had to go through the process of grieving the loss of that love and the trappings of his senses; the source of this inspiration is coming from what the ancient Greeks referred to as Agape, self-less love, which came to be translated as charity in the King James version of the Bible. It comes from the power Shakespeare has to address his fellow man, demonstrating through the work of his own creative process, his working through of the paradoxes of love, loss, mortality, and the pursuit of happiness – it is the selfless act, which Shakespeare puts before his audience.

In summation, Shakespeare should not be approached as some towering immortal God who stands above us all, quite the opposite, he is our fellow mortal. The essence of Shakespeare’s work, the hypothesis which underlies the higher hypothesis, is this acceptance of his mortality. It is the realization of those paradoxes which define the mortal life, our passions, and our desires to possess, whether it be people, things or love; it is the world that opens up as we come to the ultimate realization of having to let go of all these things – that is Shakespeare.

If we wish to know him, we need only undertake this same journe

No comments:

Post a Comment